I first encountered Anastasios (Taso) Karnazes on August 21, 2020. He was a brunette with myriad tattoos on his body sitting across from the poet Farnoosh Fathi beneath an outdoor dining vestibule in Brooklyn, NY constructed by Maya Taqueria so it would not lose business during the COVID-19 pandemic. Taso was quietly absorbed in his burrito. We did not say anything to one another. In retrospect, this moment was a foreshadowing of the alone togetherness that accompanies discovering your long-lost cousin.

Our paths crossed again on December 31, 2020 in Taso’s automobile, a 1998 BMW 318i he drove to a New Year’s Eve party in Long Island City, for which I received a last-minute invitation. In the car, Taso was concentrated on the road. On this night, the COVID-19 pandemic had been going on for approximately 10 months.

The New Year’s Eve party took place on a rooftop and contained two lightsabers. I baked a gluten-free almond cake and forgot to remove its wax paper, which someone subsequently ate. The night was cold. Taso sat across from me. Suddenly, as if moved by grace, I said something gently caustic to him. “I don’t know why I said that to you,” I remember saying. “I don’t even know you.”

Shortly thereafter, we became very good friends.

Rainbow Sonnets 20, Karnazes’ first chapbook, is comprised of 20 diptych-style poems whose 12-line sections are each divided by a tilde. On a keyboard, the tilde is located below the escape key; it is a grapheme most commonly known in English as meaning “approximately,” “about,” and “around.” While the word “escape” is not used in Rainbow Sonnets 20, the word “leave(s)” appears 12 times. “There are no leaves,” Karnazes writes, and my mind turns toward different forms of leaves—of absence, of foliage, of paper—and toward March 2020, when so many of us were unable to take leaves of absence amidst what was only the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The leaves grow long: They extend from the trees into the book I hold in my hands. I leaf through it, and then I read and reread its leaves.

I keep a copy of Rainbow Sonnets 20 on my nightstand. If I were writing a letter of recommendation for my favorite chapbook, one sentence I might include is: “A phrase that comes to mind when I think of this book is: a sad face bird watching a webcam.”

Neither Rainbow Sonnets 20 nor Karnazes is hopeful about the future of Earth. Nor am I. And I am thinking now about how the pillage of Earth by human adults reflects the ongoing objectification and abuse of children across time. To write with childlike precocity, as Karnazes does, is to acknowledge this trauma: “This is ok / In an instant / Life is ok / And then it is / And then it’s bad / And then it’s not.”

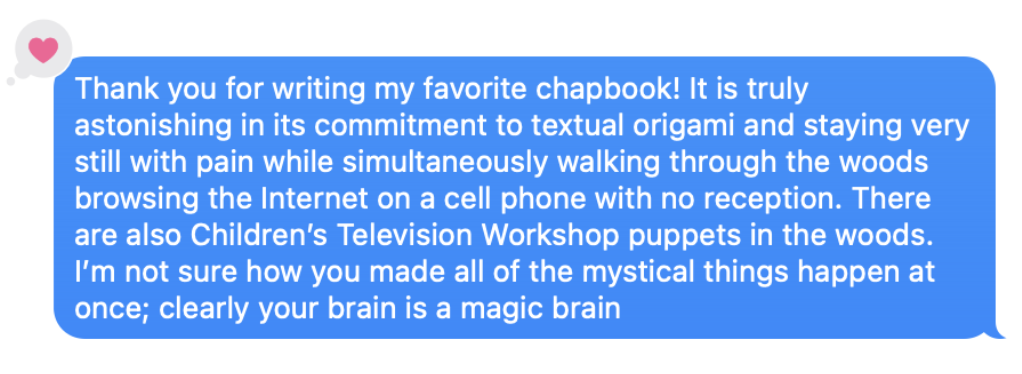

As everything must, Rainbow Sonnets 20 ends:

Order Rainbow Sonnets 20, published in an edition of 100 with cover artwork by Petra Cortright, at The Song Cave’s website.

— Claire Donato, 12.21.2021

Brooklyn, NY

![]()

—I want to answer the questions you have for me as best as I can.

—I have not prepared any questions for your interview.

—Why are you interviewing me.

—I read and was moved by your chapbook, Rainbow Sonnets 20, and we do a good job at improvising using written language and also speech. I thought we would be able to elevate your star. I also thought it would serve as a late November antidepressant.

—This is going well so far.

—I said that, and you transcribed it. Now you are laughing in the phone located behind my rose gold laptop.

—I have two computer screens that are on right now and I transcribed what you said into the Google Document tab in the Google Chrome window on the right screen. The left screen is curved but I am not using it for anything right now even though it is the dominant screen in my set up. The screen that you are in is neither of these however. You are in my phone screen which is wedged in between the number and function key rows of my keyboard, which you can hear me clack clack clack at as I typo this.

—There are a few things on my mind right now. One is a prompt and one is a thought. I will begin with the thought. My thought is that people think we are just giving our subjectivities away online, but we have so many thoughts and therefore so many subjectivities, insofar as our thoughts have minds of their own. I don’t know why we think a lot of sentences = a lot of thoughts. The mind has, like, 10,000 thoughts a day? What thoughts do we transcribe versus not. That is on my mind. Now for the prompt. The prompt is for us to transcribe what we see in the windows so our readership can glean a vivid mental photograph of us at this time, 10:11pm on Saturday, November 27, 2021. Then the interview can truly begin.

—What do you mean by windows, I am a bit confused.

—There are probably a few windows in your space right now. You could choose the window you’d like to transcribe. If I was being controlling, I would recommend that you transcribe the window of your phone and vice-versa, so we can invoke a sort of colorful depiction of ourselves for our readership.

—The first thing that I see in my phone window, or the first thing which takes my attention is Claire’s white Vitamix which is stacked on top of her refrigerator. The hard plastic of the blender pitcher is clear and clean, which is particularly moving because my own vitamix pitcher is fogged up from what I believe is some kind of residue from the spinach which I use in all my smoothies. My eyes then move down below the vitamix, remembering the white encasing as it contrasts with the black buttons, to the stickers and/or prints which fill the face of her refrigerator’s freezer door. Claire leans in to observe my airpods and obstructs the refrigerator front, though I can still make out the handles towards the far end of the door. She leans away and I see a blue spray bottle for a split before she leans back and obstructs that too. Towards the bottom of the refrigerator panel there is a blue chip clip that holds up an orange sheet of paper which is almost completely out of view, obstructed by the table claire’s laptop is positioned on as she types. I am particularly drawn to the chip clip because I really enjoy chips, but I have never invested in clips for the chips, so end up folding the bag in some kind of loose fashion that never quite works out right. If i had claires chip clip it would not be used as a magnet for the refrigerator door. I would use it properly. Claire is now disturbing the framing of her phone camera by moving it closer to her face to get a better view of something in my frame. There is a nauseating effect of her swinging my view around to do so, and I feel my observations jarred by the disturbance. [Afterward: I feel really fucked up about what I wrote here. It was very insensitive towards Claire and I take full accountability for the pain I was the grounds for, especially the part where I say she made me nauseous! Ugh!]

—The first thing I see when I look in my phone window are Taso’s AirPods. He has one in each ear although I can more clearly see the AirPod in his right ear. His AirPods are whiter than his sclera. I had to pause for a moment and look up parts of the eye. My understanding is the sclera is the white part of it. The wall behind Taso is cream colored and also there is a wooden wall underneath the painted wall—a Victorian interior design, perhaps? I am looking now at a series of what the hell are those things behind you? They look like boxes stacked atop one another with perhaps a score for a musical stacked atop them. I wonder if the score is for a Sondheim musical seeing as Sondheim died yesterday. You are wearing a shirt the color of expensive mustard and have a beard now. You still have two eyes. Where is the white tea mug that may or may not match your AirPods? You seem contemplative and it is late November. Your office chair is black and seems ergonomic but that may be a projection indicating my own desire for an ergonomic desk chair. I have been using a plastic ghost chair for too long. My posture is askew, although recently someone told me I had good posture. What are those objects to the far right of your frame? Are you wearing red lipstick? Is that a wig or your true hair? Do you have mousse in it? Oh my god, I’m now noticing there is a word on your shirt. It says Orchard and the word is embroidered on the left breast pocket area of your shirt, although there is no pocket. You furrow your brow. I am now looking again at the wooden wall and am thinking about the wooden walls in my childhood dining room. We rarely took meals in that room but occasionally celebrated Thanksgiving in it. My dad had an office in the dining room and would work on his academic papers and smoke cigarettes there. [Afterword: Taso says I should use this space to express my feelings about his involuntary micro-cruelty regarding how I nauseated him. I want to let you know I am doing okay and we talked about it.]

—I am still reflecting on my previous cruelty and want to offer an interpretation which respects your experience but also elaborates or clarifies what I think I’d meant. The nausea I experienced was not generated by the mise en scene, rather it was through what we might call a formal decision on your behalf to change the shot from static to a complicated series of pans when you picked it up and waved it around a bit. We might call this disruption a technical, rather than material, action, and I would argue the fact that it struck me almost violently is a testament to an aesthetic possibility inherent to consumer electronics which often gets put-on-vibrate by the contemporary landscape poem which eschews technics for the sake of proselytizing tree gaia Graham-Morton crypto-spiritualism.

—Are you gaslighting me? [Addendum: Taso made me ask this.]

—Notice the term “gaslighting” already relies on enlightenment tropes to construct a humanist sociality which takes the …

—What next? Taso is drinking a sip of tea. Should we talk about “the work”?

[Addendum: I think it is important for our readers to understand we conducted this interview largely in Cageian silence. I might also call this form of alone togetherness “the oceanic feeling.”]

—People often make the distinction between writing and speech, but I would like to underscore a distinction instead between typing and writing.

—Say more.

—What do you think about that?

—Do you mean that typing is different from writing? It feels like we are talking.

—What does it sound like when I say this?

—It sounds a little bit like your voice but also the sound of the keys. What does it sound like when I say this?

—I can’t hear it that well, can you speak up?

—Now you are yelling and it is unseemly for a respectful interview. Are you insane?

—What do you think?

—I don’t feel comfortable.

—Do you want to watch a Title IX training video together?

—I don’t trust yielding screen share capabilities.

—We aren’t on Zoom.

—One thing that interests me with your work is the heightened sensitivity to miniature experiences.

—A few images come to mind when I think of your work: trees, birds, a phone, lol, sad. There is a particular rhythmic quality to your work, as well, that reminds me of the Children’s Television Workshop. It is necessarily transporting. Reading it, I feel like a gifted child, but I also feel like I am experiencing carefully planned metrical patterns whilst confined within the trunk of a tree. Does this make sense?

—I was in the gifted child program at my school, were you?

—What was your teacher’s name?

—The teachers were sort of the same, we would just go to a different room when there was a math lesson and learn instead from some math specialized teacher. Whose name I can’t remember.

—I had a teacher named Mr. Busko. He taught music and sometimes smoked cigarettes with my dad.

—What did Mr. Busko’s breath smell like?

—What do you think?

—Cigarettes with your dad.

—I want to think a little bit about the phenomenon of watching someone type and then delete a thought, and then retype it. It occurs to me that this phenomenon takes place in speech but that it takes on a different quality when one is typing and another is witnessing to one’s typing.

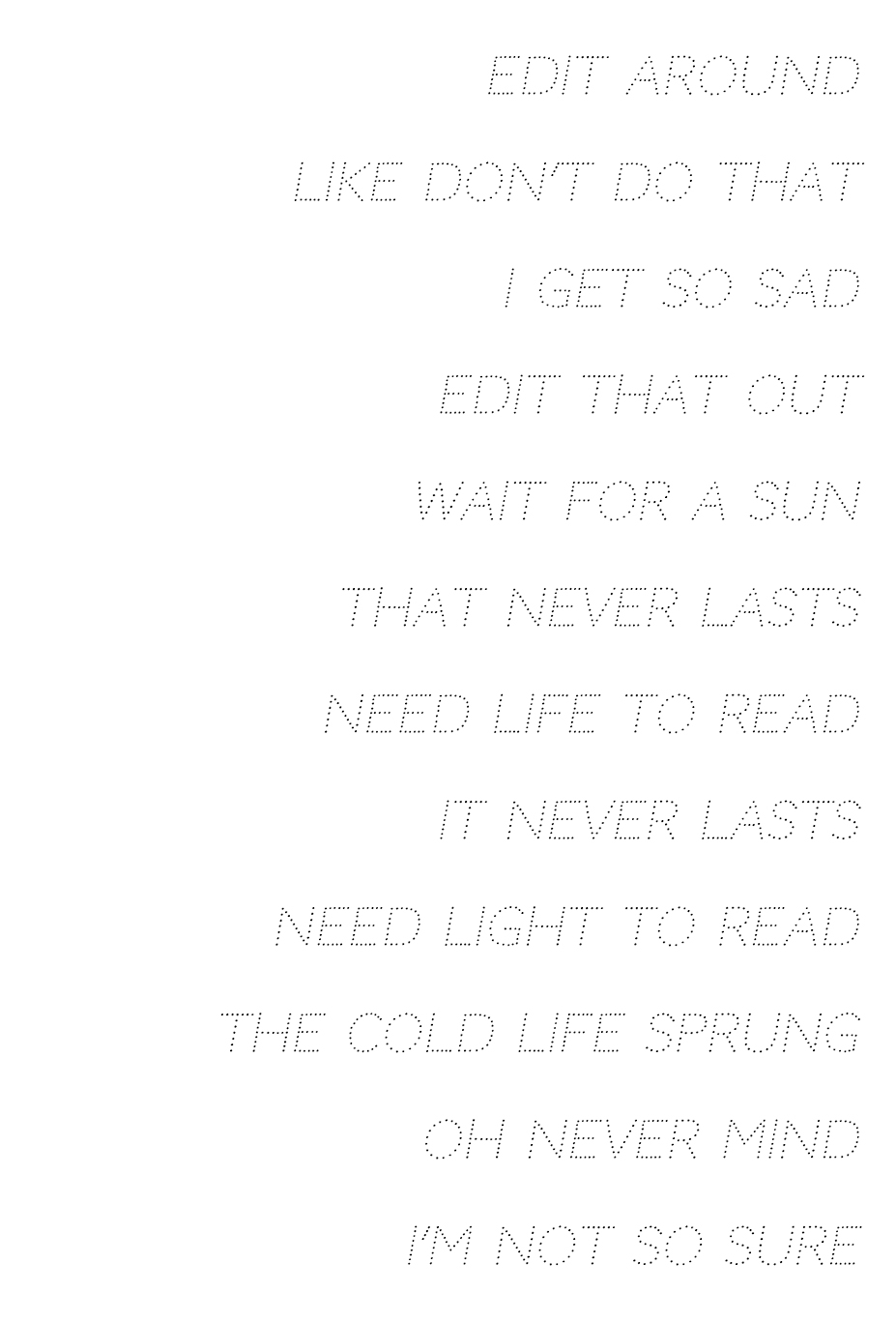

—This is especially important within the context of my work. You will have noticed a recurrence of some line “edit that out” throughout the piece, and this is in part to replicate or choreograph this experience, but it is also a formal necessity for any type of poetics which seeks to dramatize the distinction I phrased earlier.

—What are you trying to say?

—Hold on I think my dad is calling.

—Really? Or are you LARP’ing? Am I correctly using the LARP abbreviation?

—Sorry my dad was typing here for a second. What I meant to say was

![]()

—”I’m not so sure.”

—You obviously don’t take the climate crisis very seriously.

—I am now watching you drink water out of plastic.

—I am not concerned with the climate crisis, and want to aestheticize my consumer plastic waste within my poetic project.

—That bottle will outlive you, but where will it live when we’re dead?

—It will be a nice home for some cute creature.

—It could make for an opaque terrarium. Do you want to tell the readership of this interview when and where you chiefly wrote your chapbook? As in a freshman writing class, please try to be as detailed as possible in your sensory description. I really want people who weren’t there to feel like they were there, so they don’t feel left out of your writing practice. I am an only child and sharing is one of my values :)

—Thank you for being honest about where you are coming from. I promise to compassionately respond with an equal honesty but also with gratitude for your setting the stage as such. I began writing this poem in the summer of 2020, when did the pandemic start? [Addendum: I almost don’t know if I want to talk about the pandemic there. Why? Is this pain avoidance? It is not pain avoidance, but it is an aversion to the cliche of asking about when the pandemic started, since so much pandemic characterization relies on its temporal obscuring properties.]

—March 2020. Did we know one another when you began writing the poem? Or did we meet later? [Addendum: I asked Taso if he was trying to avoid pain by not wanting to talk about the pandemic. Is this pain avoidance, I asked, and he transcribed my question as if it was his own. I am feeling a little unsettled about whether or not my choice to differentiate our voices in the addendum via italics sits easy with you. Maybe it is fear, but I cannot place your affective response to this editorial choice. “In person” or in type? See I just had to italicize that for you, which makes me feel even more afraid in the moment about the editorial choice. Why? Because I want to take your decision to not italicize your voice initially as a social cue. Okay.]

—We met after I began writing this poem.

—[Addendum: Taso just instructed me to type the phrase “go on” here.]

—The poem appeared first because this longer poem I had been working on for several months needed a companion. And I was into the history of the QWERTY keyboard design, but had nowhere to place that interest in the longer poem. The mountains of North Carolina are populated with mostly pine trees.

—Is that where you grew up?

—I grew up in Charlotte, North Carolina, like the poet Lee Ann Brown. But was staying at my parents’ mountain retreat during the pandemic, since New York was a police state. There were some really great birds that came to eat at their birdfeeders. One was called an Indigo Bunting.

—I recently found a guide to birding on the street. It is inscribed to a person named Peter from “Daddy.” [Addendum: Taso now has a page from this book that depicts the parts of a bird.]

—Birds are the original typists. Their beaks contain a series of buttons which generate soundwaves based on their inputs.

![]()

—At this point in our interview, I’d like to do a check-in :) How are you feeling?

—I am feeling pretty good about chatting. How are you feeling? [Addendum: I would like to more broadly extend this check-in to this interview’s readership.]

—I am having a good time in the Google Document and like talking with you through the phone behind the computer. It is a novel interaction. I feel we are covering a lot of terrain and that this exercise is weird.

—Weird in what sense?

—It is a new way of spelunking our consciousnesses in front of one another because we normally just text. I am not sure the people reading this will really understand our process.

—I think as artists we can make a choice about how much of the process to disclose to the audience. One thing I will point out as I am noticing it is that I feel more accountable by out faces being subjected to each other as we type, moreso than the typical texting configuration. [Addendum: It occurs to me there is no experience of being subjected to the other’s face when one is texting with the other, unless consensual self-portraits are exchanged.]

—Are you trying to make deliberate facial expressions? I am not really checking in much with the phone. Now I am watching you instead of watching you type.

—I was not paying attention to my face or your face in particular, but the fact that they are both made available, as a part of the process of typing, has an impact. I may try watching the phone screen instead of the computer screen now and see how that impacts my response.

—Should we take a photograph of the mise-en-scene for our readership?

—You mean like a screenshot?

—How could we take a photograph of the computers and the cell phones set up at once? I imagine that would require moving the phone away to use the phone’s camera, but then there would be no phone to photograph.

—I think we would need a mirror.

—I have a handheld one I can go get.

—That would be great, I will try to get one as well.

[Claire and Taso break to go get mirrors]

—My mirror is extremely dirty. I think it has residual makeup on it or maybe drywall.

—I couldn’t find one but I have another idea which is to use my webcam.

[We take photographs]

![]()

Our paths crossed again on December 31, 2020 in Taso’s automobile, a 1998 BMW 318i he drove to a New Year’s Eve party in Long Island City, for which I received a last-minute invitation. In the car, Taso was concentrated on the road. On this night, the COVID-19 pandemic had been going on for approximately 10 months.

The New Year’s Eve party took place on a rooftop and contained two lightsabers. I baked a gluten-free almond cake and forgot to remove its wax paper, which someone subsequently ate. The night was cold. Taso sat across from me. Suddenly, as if moved by grace, I said something gently caustic to him. “I don’t know why I said that to you,” I remember saying. “I don’t even know you.”

Shortly thereafter, we became very good friends.

Rainbow Sonnets 20, Karnazes’ first chapbook, is comprised of 20 diptych-style poems whose 12-line sections are each divided by a tilde. On a keyboard, the tilde is located below the escape key; it is a grapheme most commonly known in English as meaning “approximately,” “about,” and “around.” While the word “escape” is not used in Rainbow Sonnets 20, the word “leave(s)” appears 12 times. “There are no leaves,” Karnazes writes, and my mind turns toward different forms of leaves—of absence, of foliage, of paper—and toward March 2020, when so many of us were unable to take leaves of absence amidst what was only the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The leaves grow long: They extend from the trees into the book I hold in my hands. I leaf through it, and then I read and reread its leaves.

I keep a copy of Rainbow Sonnets 20 on my nightstand. If I were writing a letter of recommendation for my favorite chapbook, one sentence I might include is: “A phrase that comes to mind when I think of this book is: a sad face bird watching a webcam.”

Neither Rainbow Sonnets 20 nor Karnazes is hopeful about the future of Earth. Nor am I. And I am thinking now about how the pillage of Earth by human adults reflects the ongoing objectification and abuse of children across time. To write with childlike precocity, as Karnazes does, is to acknowledge this trauma: “This is ok / In an instant / Life is ok / And then it is / And then it’s bad / And then it’s not.”

As everything must, Rainbow Sonnets 20 ends:

I love a lot

Forget it all

Nothing is left

This part is fine

Forget it fine

A love is left

Nothing a lot

This part is fine

I love it fine

Nothing is all

Forget a lot

This part is fine

I interviewed Karnazes, who now lives in Troy, NY, via Google Docs and FaceTime for approximately six hours in late November and early December 2021. During the longest stretch of our interview, he wore a brown plaid flannel shirt with buttons. As is reflected in the transcript below, our interview included numerous peaceful stretches of so-called silence wherein we typed together.Forget it all

Nothing is left

This part is fine

Forget it fine

A love is left

Nothing a lot

This part is fine

I love it fine

Nothing is all

Forget a lot

This part is fine

Order Rainbow Sonnets 20, published in an edition of 100 with cover artwork by Petra Cortright, at The Song Cave’s website.

— Claire Donato, 12.21.2021

Brooklyn, NY

—I want to answer the questions you have for me as best as I can.

—I have not prepared any questions for your interview.

—Why are you interviewing me.

—I read and was moved by your chapbook, Rainbow Sonnets 20, and we do a good job at improvising using written language and also speech. I thought we would be able to elevate your star. I also thought it would serve as a late November antidepressant.

—This is going well so far.

—I said that, and you transcribed it. Now you are laughing in the phone located behind my rose gold laptop.

—I have two computer screens that are on right now and I transcribed what you said into the Google Document tab in the Google Chrome window on the right screen. The left screen is curved but I am not using it for anything right now even though it is the dominant screen in my set up. The screen that you are in is neither of these however. You are in my phone screen which is wedged in between the number and function key rows of my keyboard, which you can hear me clack clack clack at as I typo this.

—There are a few things on my mind right now. One is a prompt and one is a thought. I will begin with the thought. My thought is that people think we are just giving our subjectivities away online, but we have so many thoughts and therefore so many subjectivities, insofar as our thoughts have minds of their own. I don’t know why we think a lot of sentences = a lot of thoughts. The mind has, like, 10,000 thoughts a day? What thoughts do we transcribe versus not. That is on my mind. Now for the prompt. The prompt is for us to transcribe what we see in the windows so our readership can glean a vivid mental photograph of us at this time, 10:11pm on Saturday, November 27, 2021. Then the interview can truly begin.

—What do you mean by windows, I am a bit confused.

—There are probably a few windows in your space right now. You could choose the window you’d like to transcribe. If I was being controlling, I would recommend that you transcribe the window of your phone and vice-versa, so we can invoke a sort of colorful depiction of ourselves for our readership.

—The first thing that I see in my phone window, or the first thing which takes my attention is Claire’s white Vitamix which is stacked on top of her refrigerator. The hard plastic of the blender pitcher is clear and clean, which is particularly moving because my own vitamix pitcher is fogged up from what I believe is some kind of residue from the spinach which I use in all my smoothies. My eyes then move down below the vitamix, remembering the white encasing as it contrasts with the black buttons, to the stickers and/or prints which fill the face of her refrigerator’s freezer door. Claire leans in to observe my airpods and obstructs the refrigerator front, though I can still make out the handles towards the far end of the door. She leans away and I see a blue spray bottle for a split before she leans back and obstructs that too. Towards the bottom of the refrigerator panel there is a blue chip clip that holds up an orange sheet of paper which is almost completely out of view, obstructed by the table claire’s laptop is positioned on as she types. I am particularly drawn to the chip clip because I really enjoy chips, but I have never invested in clips for the chips, so end up folding the bag in some kind of loose fashion that never quite works out right. If i had claires chip clip it would not be used as a magnet for the refrigerator door. I would use it properly. Claire is now disturbing the framing of her phone camera by moving it closer to her face to get a better view of something in my frame. There is a nauseating effect of her swinging my view around to do so, and I feel my observations jarred by the disturbance. [Afterward: I feel really fucked up about what I wrote here. It was very insensitive towards Claire and I take full accountability for the pain I was the grounds for, especially the part where I say she made me nauseous! Ugh!]

—The first thing I see when I look in my phone window are Taso’s AirPods. He has one in each ear although I can more clearly see the AirPod in his right ear. His AirPods are whiter than his sclera. I had to pause for a moment and look up parts of the eye. My understanding is the sclera is the white part of it. The wall behind Taso is cream colored and also there is a wooden wall underneath the painted wall—a Victorian interior design, perhaps? I am looking now at a series of what the hell are those things behind you? They look like boxes stacked atop one another with perhaps a score for a musical stacked atop them. I wonder if the score is for a Sondheim musical seeing as Sondheim died yesterday. You are wearing a shirt the color of expensive mustard and have a beard now. You still have two eyes. Where is the white tea mug that may or may not match your AirPods? You seem contemplative and it is late November. Your office chair is black and seems ergonomic but that may be a projection indicating my own desire for an ergonomic desk chair. I have been using a plastic ghost chair for too long. My posture is askew, although recently someone told me I had good posture. What are those objects to the far right of your frame? Are you wearing red lipstick? Is that a wig or your true hair? Do you have mousse in it? Oh my god, I’m now noticing there is a word on your shirt. It says Orchard and the word is embroidered on the left breast pocket area of your shirt, although there is no pocket. You furrow your brow. I am now looking again at the wooden wall and am thinking about the wooden walls in my childhood dining room. We rarely took meals in that room but occasionally celebrated Thanksgiving in it. My dad had an office in the dining room and would work on his academic papers and smoke cigarettes there. [Afterword: Taso says I should use this space to express my feelings about his involuntary micro-cruelty regarding how I nauseated him. I want to let you know I am doing okay and we talked about it.]

—I am still reflecting on my previous cruelty and want to offer an interpretation which respects your experience but also elaborates or clarifies what I think I’d meant. The nausea I experienced was not generated by the mise en scene, rather it was through what we might call a formal decision on your behalf to change the shot from static to a complicated series of pans when you picked it up and waved it around a bit. We might call this disruption a technical, rather than material, action, and I would argue the fact that it struck me almost violently is a testament to an aesthetic possibility inherent to consumer electronics which often gets put-on-vibrate by the contemporary landscape poem which eschews technics for the sake of proselytizing tree gaia Graham-Morton crypto-spiritualism.

—Are you gaslighting me? [Addendum: Taso made me ask this.]

—Notice the term “gaslighting” already relies on enlightenment tropes to construct a humanist sociality which takes the …

—What next? Taso is drinking a sip of tea. Should we talk about “the work”?

[Addendum: I think it is important for our readers to understand we conducted this interview largely in Cageian silence. I might also call this form of alone togetherness “the oceanic feeling.”]

—People often make the distinction between writing and speech, but I would like to underscore a distinction instead between typing and writing.

—Say more.

—What do you think about that?

—Do you mean that typing is different from writing? It feels like we are talking.

—What does it sound like when I say this?

—It sounds a little bit like your voice but also the sound of the keys. What does it sound like when I say this?

—I can’t hear it that well, can you speak up?

—Is this better?

—Now you are yelling and it is unseemly for a respectful interview. Are you insane?

—What do you think?

—I don’t feel comfortable.

—Do you want to watch a Title IX training video together?

—I don’t trust yielding screen share capabilities.

—We aren’t on Zoom.

—One thing that interests me with your work is the heightened sensitivity to miniature experiences.

—A few images come to mind when I think of your work: trees, birds, a phone, lol, sad. There is a particular rhythmic quality to your work, as well, that reminds me of the Children’s Television Workshop. It is necessarily transporting. Reading it, I feel like a gifted child, but I also feel like I am experiencing carefully planned metrical patterns whilst confined within the trunk of a tree. Does this make sense?

—I was in the gifted child program at my school, were you?

—What was your teacher’s name?

—The teachers were sort of the same, we would just go to a different room when there was a math lesson and learn instead from some math specialized teacher. Whose name I can’t remember.

—I had a teacher named Mr. Busko. He taught music and sometimes smoked cigarettes with my dad.

—What did Mr. Busko’s breath smell like?

—What do you think?

—Cigarettes with your dad.

—I want to think a little bit about the phenomenon of watching someone type and then delete a thought, and then retype it. It occurs to me that this phenomenon takes place in speech but that it takes on a different quality when one is typing and another is witnessing to one’s typing.

—This is especially important within the context of my work. You will have noticed a recurrence of some line “edit that out” throughout the piece, and this is in part to replicate or choreograph this experience, but it is also a formal necessity for any type of poetics which seeks to dramatize the distinction I phrased earlier.

—What are you trying to say?

—Hold on I think my dad is calling.

—Really? Or are you LARP’ing? Am I correctly using the LARP abbreviation?

—Sorry my dad was typing here for a second. What I meant to say was

—”I’m not so sure.”

—You obviously don’t take the climate crisis very seriously.

—I am now watching you drink water out of plastic.

—I am not concerned with the climate crisis, and want to aestheticize my consumer plastic waste within my poetic project.

—That bottle will outlive you, but where will it live when we’re dead?

—It will be a nice home for some cute creature.

—It could make for an opaque terrarium. Do you want to tell the readership of this interview when and where you chiefly wrote your chapbook? As in a freshman writing class, please try to be as detailed as possible in your sensory description. I really want people who weren’t there to feel like they were there, so they don’t feel left out of your writing practice. I am an only child and sharing is one of my values :)

—Thank you for being honest about where you are coming from. I promise to compassionately respond with an equal honesty but also with gratitude for your setting the stage as such. I began writing this poem in the summer of 2020, when did the pandemic start? [Addendum: I almost don’t know if I want to talk about the pandemic there. Why? Is this pain avoidance? It is not pain avoidance, but it is an aversion to the cliche of asking about when the pandemic started, since so much pandemic characterization relies on its temporal obscuring properties.]

—March 2020. Did we know one another when you began writing the poem? Or did we meet later? [Addendum: I asked Taso if he was trying to avoid pain by not wanting to talk about the pandemic. Is this pain avoidance, I asked, and he transcribed my question as if it was his own. I am feeling a little unsettled about whether or not my choice to differentiate our voices in the addendum via italics sits easy with you. Maybe it is fear, but I cannot place your affective response to this editorial choice. “In person” or in type? See I just had to italicize that for you, which makes me feel even more afraid in the moment about the editorial choice. Why? Because I want to take your decision to not italicize your voice initially as a social cue. Okay.]

—We met after I began writing this poem.

—[Addendum: Taso just instructed me to type the phrase “go on” here.]

—The poem appeared first because this longer poem I had been working on for several months needed a companion. And I was into the history of the QWERTY keyboard design, but had nowhere to place that interest in the longer poem. The mountains of North Carolina are populated with mostly pine trees.

—Is that where you grew up?

—I grew up in Charlotte, North Carolina, like the poet Lee Ann Brown. But was staying at my parents’ mountain retreat during the pandemic, since New York was a police state. There were some really great birds that came to eat at their birdfeeders. One was called an Indigo Bunting.

—I recently found a guide to birding on the street. It is inscribed to a person named Peter from “Daddy.” [Addendum: Taso now has a page from this book that depicts the parts of a bird.]

—Birds are the original typists. Their beaks contain a series of buttons which generate soundwaves based on their inputs.

—At this point in our interview, I’d like to do a check-in :) How are you feeling?

—I am feeling pretty good about chatting. How are you feeling? [Addendum: I would like to more broadly extend this check-in to this interview’s readership.]

—I am having a good time in the Google Document and like talking with you through the phone behind the computer. It is a novel interaction. I feel we are covering a lot of terrain and that this exercise is weird.

—Weird in what sense?

—It is a new way of spelunking our consciousnesses in front of one another because we normally just text. I am not sure the people reading this will really understand our process.

—I think as artists we can make a choice about how much of the process to disclose to the audience. One thing I will point out as I am noticing it is that I feel more accountable by out faces being subjected to each other as we type, moreso than the typical texting configuration. [Addendum: It occurs to me there is no experience of being subjected to the other’s face when one is texting with the other, unless consensual self-portraits are exchanged.]

—Are you trying to make deliberate facial expressions? I am not really checking in much with the phone. Now I am watching you instead of watching you type.

—I was not paying attention to my face or your face in particular, but the fact that they are both made available, as a part of the process of typing, has an impact. I may try watching the phone screen instead of the computer screen now and see how that impacts my response.

—Should we take a photograph of the mise-en-scene for our readership?

—You mean like a screenshot?

—How could we take a photograph of the computers and the cell phones set up at once? I imagine that would require moving the phone away to use the phone’s camera, but then there would be no phone to photograph.

—I think we would need a mirror.

—I have a handheld one I can go get.

—That would be great, I will try to get one as well.

[Claire and Taso break to go get mirrors]

—My mirror is extremely dirty. I think it has residual makeup on it or maybe drywall.

—I couldn’t find one but I have another idea which is to use my webcam.

[We take photographs]

Claire Donato is a writer and multidisciplinary artist. She is the author of two books: Burial (Tarpaulin Sky Press), a novella, and The Second Body (Poor Claudia), a collection of poems. She also wrote the introduction to The One on Earth: Selected Works of Mark Baumer (Fence Books). Recent writing has appeared or is forthcoming in The Chicago Review, Fence, Forever, GoldFlakePaint, The Brooklyn Rail, DIAGRAM, The Believer, BOMB, and Harp & Altar. Beyond the page, her art practice includes illustration, 35mm photography, video, and songwriting. She teaches psychoanalysis-inflected courses and advises theses in the MFA/BFA Writing Program at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where she received the 2020 Distinguished Teacher Award.

Anastasios Karnazes is a doctoral student in English at SUNY Albany and editor of Theaphora Editions.

Anastasios Karnazes is a doctoral student in English at SUNY Albany and editor of Theaphora Editions.