HEADLAND FOREVER Ashleigh Bryant Phillips

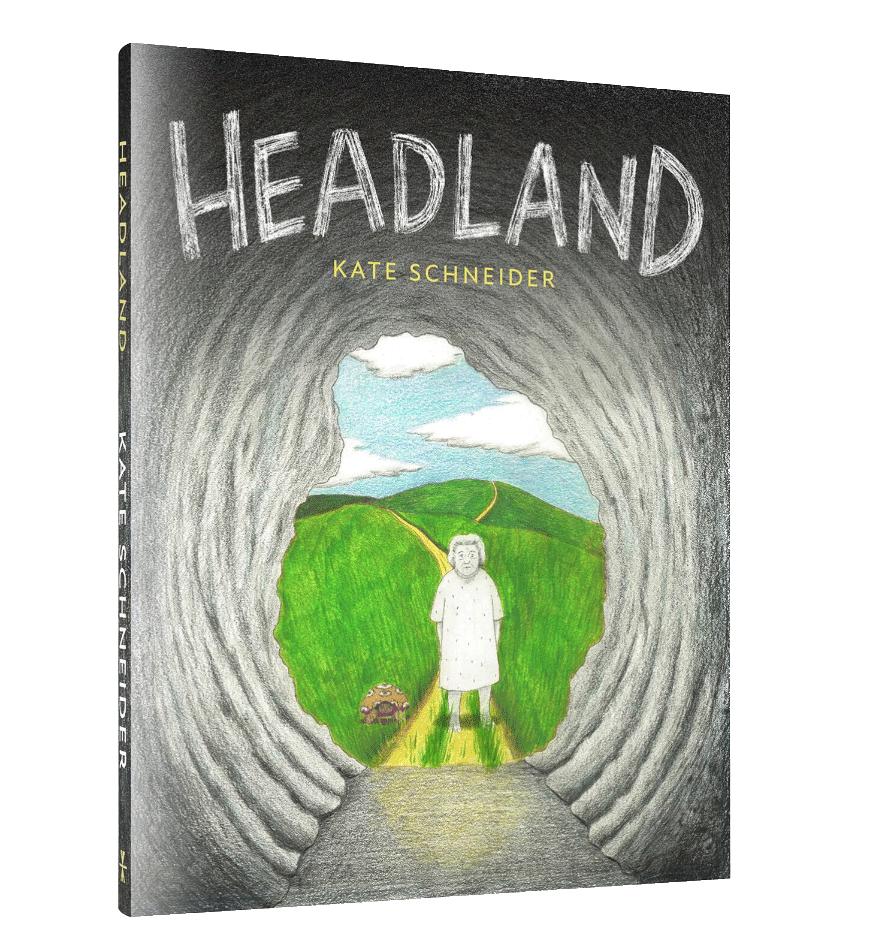

There’s an elderly woman on the cover. She’s wearing a hospital gown. There’s a tortoise beside her. They’re both standing at the opening of a cave, staring straight inside it.

I can count on one hand how many times he ever looked me in the eyes then. Once in a blue moon. I was always waiting for it, wanting it. Never expecting it. Always hoping.

I didn’t know how much of him was left. And there was no way to tell. If he was there, was he afraid? Was he in pain? Was he lonely? Was he afraid? Was he in pain? Was he lonely? Where was he? Where was he? Where was he? Look at me daddy, I’m trying to tell you I love you. Do you hear me? I love you. What do you want me to tell you about? The millpond? The weather? My writing? The book you told me I could write? Daddy, I’m telling you. What do you think? Are you proud? Do you feel loved? Can you hear me? Will you look at me? Can you look at me? Are you here? Where are you? Are you here daddy? Someone tell me where he is. Where did he go?

***

I painted June’s fingernails. She was always in awe of it. Held her hands out in astonishment. She’d worked in a chicken plant. Raised three sons. None of them came to see her but she believed they did.

Ruby would ask me over and over how old I was. She had multiple pocketbooks and liked to stay in her room. She had a print of a life-size baby on her wall. She was always trying to reach out and grab it. She always wanted me to sit next to her in the dining room. Sometimes she’d eat her tea like soup with a spoon.

Emily believed her daddy lived right down the road (hall). She thought I was her sister, she took my arm, we were sneaking off to go to the dance. We were gonna meet the thrilling boys Mama and Daddy didn’t want us around. We passed by the nurses station and Emily asked them for something strong. They gave us shots (water) in medicine cups. Emily threw back her shot, slammed the cup on the counter. She looked at me with huge eyes, all-alive and said, “Shew, that was nasty!” Like it was the strongest, sharpest thing she’d tasted in the whole world. Then she laughed, said “We’ve gotta find a mint ‘round here…daddy’s gonna smell it on us.”

At one point, my daddy had these realities too. These magic places. But I wasn’t there to play with him. I was away in grad school, trying to do a good job. Here I was now, though, here at the end. Terrified he was afraid, in pain, lonely. Hoping somehow, someway he was somewhere else, somewhere better. He had to be.

Kate Schneider made Headland. Her bio in the back of the book says she’s an “artist, writer, and therapist living and working in Philadelphia.”

I followed her on Instagram and sent her a message:

Dear Kate,

I just finished Headland last night and I can’t tell you how beautiful and powerful of an experience it was. I’m a short story writer myself–my daddy passed away from Alzheimer’s and in the end when he lost his ability to walk and talk, I often thought about what was happening in his imagination–hoping he was in no world of pain in his mind. Hospice always says that hearing is the last to go, but I also wanna believe that imagination is also there at the very end too. I’ve struggled and struggled to write about it in my fiction. Headland not only gave me hope, but it showed me that–yes–our imagination IS STILL THERE. And there is a way to show the brutality, mystery, and grace of the end–with dignity.

Thank you so much for your brave and honest work. I’m gonna be recommending it to everyone I know. Congrats on such an incredible book!

<3 <3,

Ashleigh

I wanted to see what others were saying about Headland but I couldn't find a thing. So I decided I’d write about it myself. People needed to know.

But I didn’t want to approach Kate until I had a nice magazine interested in it. So I started pitching it: I’m going to write an essay that will explore the creation of HEADLAND the book, and discuss HeadLand as a place that’s awaiting all of us. The essay will tell Kate’s story. It will wrestle with the brutality and mystery of death as well as how memory, language, and communication make the self. It will also consider grief as a pathway to creation and discuss the intrinsic power of imagination—ultimately asking the question: “Is the imagination the last destination of the self?”

I didn’t hear anything back from the editors.

I looked at Kate’s instagram posts: Moss and beauty berries. Miniature clay pies, mirrors she’d made. Tulips, creek beds, monstera leaves. Seashells, kittens, a lemon blueberry cake. Sexy selfies in clown makeup, with dangling grape earrings, in windows reflecting clouds, trees. Glow in the dark stars.

oh have you

looked wistfully into

the flushed bodies of the flowers? have you stood

staring out over the swamps, the swirling rivers

where the birds like tossing fires

flash through the trees, their bodies

exchanging a certain happiness

in the sleek, amazing

humdrum of nature’s design —

blood’s heaven, spirit’s haven, to which

you cannot belong

Then Kate posted on her Instagram:

I had a brain tumor removed just over a week ago. The operation went well and I’ll have to start treatment soon. I’m optimistic, I feel positive and I have a great team. I’m lucky to have amazing support. Willy has been my rock.

Because of the trauma to my brain, I feel like I’m reading my book Headland for the first time. Since the operation I now enter it as a reader. I feel less like the author of the book. I am closer to Ruth.

Hey there Kate,

This is Ashleigh Bryant Phillips—I reached out to you on insta after reading HEADLAND. I keep it on my coffee table and show it to everyone who comes in my apartment. :)

I know you’re recovering from some serious surgery these days…but I wanted to throw this idea out there for you to think on…for whenever in the future you feel ready of course.

I’d absolutely love to interview you or write a feature on your work.

I live in Baltimore and would happily take the train to you in Philadelphia so we can talk IRL.

If this sounds appealing to you, let me know!

Once I get the green light from you, I’ll get my agent to start pitching some places. And then we can schedule a meet up.

Your work is so smart and forces folks to think about uncomfortable but very real parts of life…parts that are often overlooked. I mean I sure don’t see many working artists today in my corner of the world confronting death and life in such a beautiful/colorful way. And I would love for others to experience what you’ve created so far.

Obviously, if you would rather not interview, I respect that too. Because your work already says so much. <3

Just let me know what you think…and absolutely no rush on this either.

Take care—wishing you all sunny days and blossoms.

Kindly,

Ashleigh

Hi Ashleigh,

Yes yes yes.

I am recovering from brain surgery but I feel my scope is getting wider each day and I know that I will be up for it.

The 9th -16th and then the 20th-22nd should work for me. After I start chemo and I’ll be brain foggy etc. Of course I could do it after, just let me know. I spend six weeks doing chemo.

I really appreciate this!!! It is so beautiful.

Best,

Kate

***

We met in West Philly at a Lebanese bakery. When I asked her “How’s it going?” I can’t remember if she said, “Well I’ve got cancer,” or, “Well I’m dying of cancer.” But it was one of the two. Matter of fact, direct.

She was wearing a bucket hat. Her hair was gone. She started telling me about the fertility shots she’d just given herself that morning. She was in the process of freezing her eggs. So she could have future babies someday. And she’d just got engaged too. Everything was moving so fast now.

“Headland came out in February, I found out I was sick April 11,” she said. “I had a week of brain fog. I was like oh it’s psychological, neurological, who’s to say… then I had a seizure…a week later I had my brain surgery…and a week after that I found out that I had a tumor, a mass, it was a glioblastoma–5% survival rate.” She stopped and then whistled, the sound like when a cartoon character is overwhelmed in a movie.

Glioblastoma isn’t inherited. It pops up sporadically. There is no rhyme or reason, its causes are unknown.

But this is not a story about dying.

Kate worked on Headland for six years. She started it her senior year of undergrad. She studied English, took art classes on the side. She got to workshop it a little, but everyone else was working on novels, no one really ‘got’ what she was doing.

There were the illustrations. Kate cites the brutality of The Snowman by Raymon Briggs. Posy Simmonds’ realistic depictions of the mundane. And how Quentin Blake’s scribbles were simply detailed but alive with movement. Or all that’s fired in the imagination when Pingu sips his drink from a straw. All stories with no language.

And there was the story Kate was trying to tell. When she turned in the project for her thesis, it was more of a bildungsroman. With Kate as the main character, and her mom and grandma, Eileen, in supporting roles. But it wasn’t there yet. How could Kate tell her story with no language?

Then Kate started working with a woman with dementia. Her name was Audrey.

Audrey lived in an apartment in Rittenhouse, it overlooked the park. Kate would wake her up in the morning, butter her two halves of an English muffin, make sure she took her pills. They’d have tea and then coffee after lunch. They’d eat together but mostly Audrey wanted to be alone. “She loved being on her own,” Kate said.

After this time with Audrey, some big developments happened for Kate

1. She went back to school and got a Masters in Clinical Social Work

and

2. She revisited her thesis project. Kate took herself out of it altogether. And she took some of Audrey and her grandmother, Eileen, creating Ruth.“I wanted to challenge myself to get inside Ruth’s head,” Kate said, “What is my story of her story?” Ruth, a woman recovering from a stroke, a woman who can’t decipher language, who hears words with no meaning, sees words with no meaning, who waits for life to flit, fly outside the window.

Kate queried Headland all on her own, it didn’t get many responses. “People would ask ‘What’s it about?’ and I’d say, ‘An old woman.’ And then when people would ask more questions, I figured they’d be worth telling the story to. That made me feel less alone. And I was able to figure out pretty quickly who was worth telling and who was not.”

While she waited for Headland to get picked up, Kate made a small picture book from the point of view of a prepubescent snail. Dew Drop Diary was published with F.I.N.E. editions in September 2021. It’s exuberant, poetic and pure. “I wanted the cover to have slippery snail mucus on it,” she said. And it does.

After Dew Drop Diary, F. U. Press, an imprint of Fantagraphics, was interested in Headland.

At this point, I’d like you to know that I recorded my conversation with Kate. I’m referring back to it as I write. In my memory, birds were chirping when I met Kate but I’m worried that I made it up. When I listen back to the recording, I realize it’s true.

…there’s another word that i’m looking for that’s like…desperately…sorta…help me

…what was I saying...oh language

...fuck…brain fog

As I listen back, Kate’s often struggling to find the right word. She’s stopping mid-explanation. She claps her hands out of frustration. I try to help when I can but often I don’t know what she’s trying to tell me. There’s long pauses where I wait for her, trying to sense if she wants me to change the subject altogether.

I don’t want to because I’m here with Kate. But I can’t help it, I think of my daddy. In the beginning of his Alzheimer’s, I saw him just like this, looking for “the word.” He’d ball up his fist, sling it into his other palm, over and over. Like he was about to beat somebody up. Like he knew the words were only gonna get harder and harder to find. Until there were no words–just his slinging fist, the sound of the hit. A muffled clap. A trap he couldn't get out of.

Kate’s struggling on a word.

I pull out a copy of Headland and put it in between us.

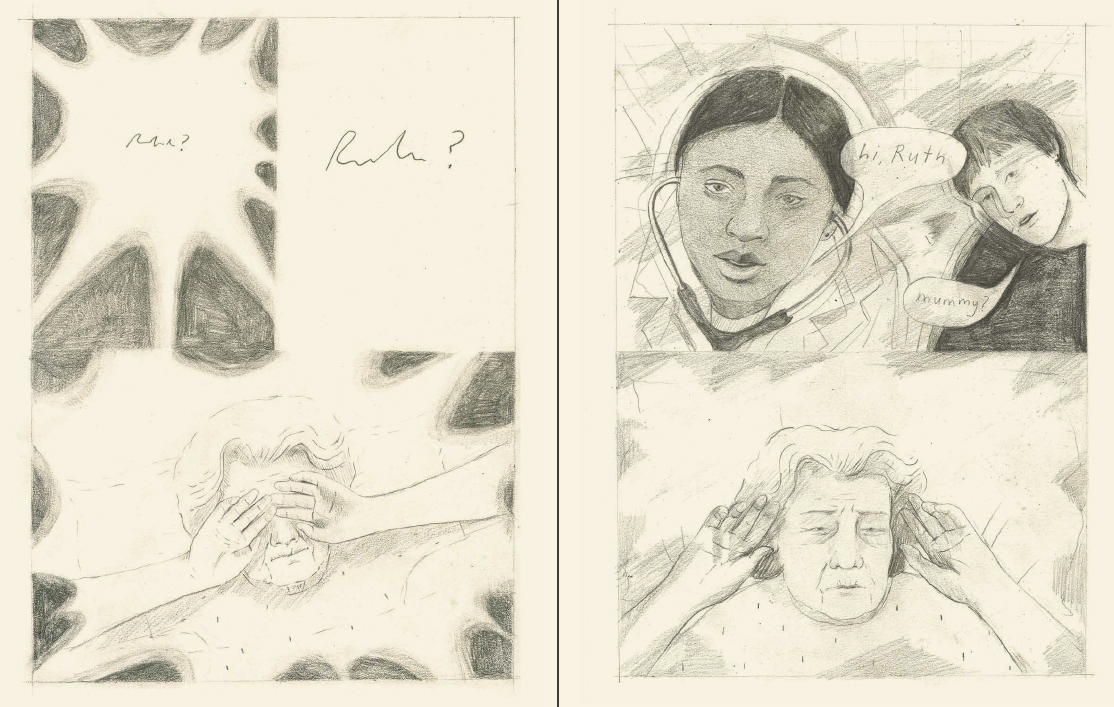

I turn to the part where Ruth can’t understand the nurses. Kate’s illustrated it with lines of indistinguishable scribble. Kate runs her finger over the lines. “I have a different perspective on this now that I’ve gone through it.”

Then I flip to the part where Ruth refuses a catheter. “I think the question that should have been asked is ‘Are you ready to go?’ And you have to bear the truth of that,” Kate says. “Medicine prioritizes safety, but safety at what cost? Safety at the cost of humor? At the cost of dignity? At the cost of comfort? At the cost of poetry?”

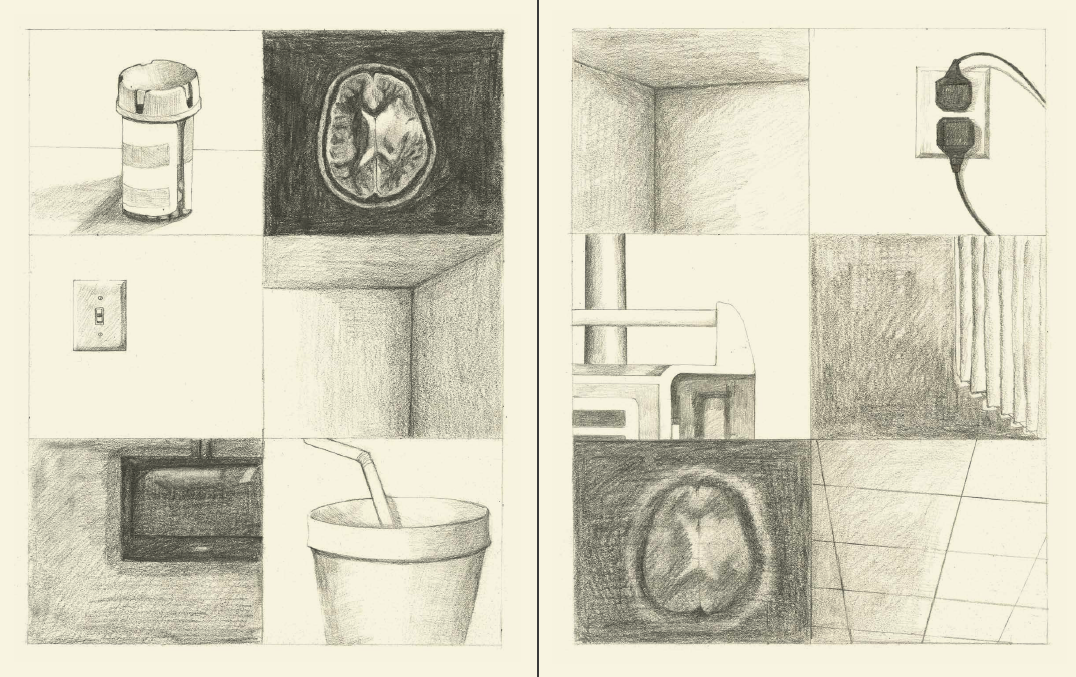

I go to the part where Ruth is bed bound and repeatedly focusing on the right hand corner of the wall, the bottom left corner of the mounted TV, the space where the blinds meet the windowsill, the lightswitch, the styrofoam cup, the ceiling tiles.

“There’s this visual scope with dementia and trauma to the brain that allows you to meditate on just one single thing and I have brain cancer and I don’t know if I’ll live or die but there is this way that peace descends onto you that when you’re brushing your teeth, all you're doing is brushing your teeth,” Kate says.

There’s a long pause.

“I know that your father died and I think that there is a possibility to imagine what other worlds he could be having…like what life could be like for him.”

My daddy worked in construction. He repaired bulldozers and cranes and excavators. He was always finding things in the dirt. One day he came home with a baby turtle. He was my first pet. I was still in diapers, had just started walking. We put the turtle in an aluminum pan with some water, sat him in the living room, gave him some leaves of grass.

Even then, I knew he couldn’t stay with us like that. He’d never be happy. We all knew that. But Daddy wanted me to see him. He showed me his lil claws, his yellow belly. I’d never seen eyes so gold.

Another thing that was happening when I met Kate was that her phone kept ringing and interrupting her train of thought. Calls from the doctors about all her appointments, egg freezing, upcoming chemo, and texts from friends: how’re you doing, sending you support, etc. etc.

But despite how fast Kate’s life was moving with all the interruptions and redirections and words getting lost and found, she looked at me, out of the blue, not missing a beat and said, “We’re not asking the hard questions and we’re not asking them enough. We don’t ask the hard questions because we don’t want to know the answers because we’re terrified of death.”

“Do you think the imagination is the last destination of the self?” I asked her.

“Absolutely,” she said. “Lynda Barry has that quote: ‘You can’t have memory without imagination and you can have imagination without memory.’ So there’s this shifting duality, you’re alway recreating your memories. Every time you remember something you’re shifting it so you’ll never truly remember anything in its purest form. That’s why you try to protect your most precious memories and tell yourself don’t go there because you want to remember it. But then there’s this fuck it attitude where it’s like I can be this portal to…”

Kate paused for a while. She noticed a dog walking past, she pointed it out to me.

“There’s this flow state that happens when you’re creating which is this absolutely magical, elusive nobody-move-anything-I’m-trying-to-capture-something mode and I think that actually has a lot in common with the self-protective mechanism that fires up when there is trauma to the brain,” Kate said. “Before the scope widens, there is this meditation, primacy. I think grief and loss do certainly get processed through sensory images. When the language is suppressed and the image center is elevated.”

Her brain fog seemed to be doing much better. We were outside another bakery in West Philly. We both got matchas. The birds in the trees around us were talk-talking back and forth. And timers went off on Kate’s phone to remind her to take Zofran. She’d started chemo.

She told me she’d been to visit her cousins and none of them could say the word cancer. How it made her feel invisible.

Her mom had just given her a journal. “Writing’s always been like my fort, my treehouse that I can climb up to. And I’m shrouded in safety. I can look down and see my life from a distance. And then when I’m done seeing it from that perspective, I can leave from up there and come back down and live my life. There is this calm in getting closer to yourself. And I’m missing that right now and I know I’m missing that right now because I’m feeling really untethered and I know there’s a reason why. I’m scared. I’m scared to get in touch with that part of myself but I know that it’s necessary. I’m scared and I know it’s necessary. Rather than I’m scared but I know it’s necessary. I can hold two things at the same time.”

I noticed there were two little blue birds fighting for nibbles under the table next to us. Kate stopped talking mid-sentence when she saw them.

“I need to get better at recognizing birds,” I said.

“Me too,” she said.

I wanted to spend more time with Kate. I wanted to be her new best friend. I wanted to go to Sephora with her and try on all the fun eyeshadows we could find.

Kate’s alarm went off again and we had to go back to her apartment so she could take her meds. She asked me what magazines I’d pitched this essay to and when I thought I’d have it done. There were no easy answers.

I wondered Will this be the last time I see her?

I wondered Is she imagining her Headland? What’s there? What does it look like? Where is she going?

“I don’t know how to end this piece,” I said.

“End it with the birds,” she said.

My first pet, that turtle–he wasn’t with us for long. The next night, after supper, me and Daddy went out behind the house, tipped the pan into the tadpole ditch. The turtle slid into the water. Daddy picked me up so I could see.

The last time I saw Kate, she told me a story about Audrey. Audrey’s husband had recently passed and when Audrey would sit alone by the window, she’d look up at the clouds and move them with her hands. She’d look for a place where the clouds gave way, where her husband could recline and relax. If she saw a spiky cloud, she’d smooth it. And then she’d finally hone in on a cloud and say, “That’s the one.”

Headland existed before death.

Headland exists now forever.

Kate told me, “To be seen is more primary than to be loved.” So thank you for reading. For seeing Kate. And me and my daddy too. And the dog in Philadelphia, and the snail, the trees, the turtles, and the birds.

Hear them? Look, there’s two birds flitting and jumping in some dust. How old do you think they are? Let’s say they’ve just been born this year. Let’s say they’ve still got a baby shampoo smell about them.

Ashleigh Bryant Phillips is from Woodland, North Carolina. She wrote Sleepovers. Stories from it appear in the Paris Review and the Oxford American.

Kate Schneider is an artist, writer and therapist living and working in Philadelphia. Her books include Dew Drop Diary (F.I.N.E. Editions, 2021) and Headland (Fantagraphics, 2022). Her work has appeared in American Chordata and The Rumpus.